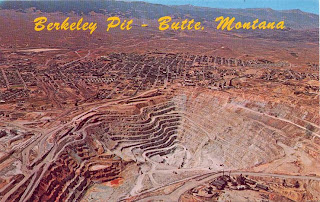

If you ever happen to find yourself on

the campus of Montana Tech, in Butte, and your eyes happen to wander

to the east, your gaze will be greeted by a stunning scenic display.

Historic gallows frames from the old mining days dot the foreground,

while the hillside behind them appears as artistic horizontal bands

of orange, red, yellow, and brown. I know of at least one artist who

made that hillside the subject of a rather pretty series of oil

paintings.

That hillside, of course, is the

Berkley Pit: America's biggest superfund site and once known as “the

richest hill on earth.” Those beautiful bands of color are the end

result of environmental pillaging on an almost unimaginable scale;

the lovely hues that paint the terraced hillside come from over a

century of mining waste and pollution. The richest hill on earth has

become its foulest pit, but from a distance it looks sorta pretty.

If you get a little closer, down inside of it, say, the view isn't

nearly so pleasant.

This is by way of making a point about

perspective, description and knowledge. The perspective from which

one views the world has necessary consequences on one's description

of the world. One's description of the world dictates which facts

about the world one can become aware of, and which facts one cannot

(because they fall outside of one's description). Any economist

necessarily views the economy from a particular perch within the

economic system which s/he is describing. The location of this perch

is an over-determining factor in the economist's economic thinking

and outlook. It largely determines which phenomena they see as

problematic and which as salutary, which problems they consider

relatively minor, to be safely ignored, and which need immediate

addressing.

Most of those whose occupations consist

of describing the economy and its functioning occupy perches that

are, at the very least, situated well within the top half of the

income distribution. Even relatively low-paid adjunct professors, if

not especially affluent, are at least part of the white-collar,

professional world. This uniformity of perspective has important

effects on economic theory and knowledge. It is as if economists

were trying to describe the Berkley Pit, but never venturing any

closer to it than the Montana Tech campus. This is not to imply that

there is nothing important that one might discover from that

perspective, but rather to point out that many important aspects of

reality are simply not accessible from that vantage point.

In the same way, economists whose

entire experience of the labor market consists of holding one or

another academic post, can hardly be expected to have much to

contribute to discussions about the low-wage service sector. From

behind a desk in the ivory tower the psychological suffering faced by

“the working poor” on a daily basis probably doesn't seem like

such a big deal. For a tenured academic, it might be difficult to

understand the psychic toll that a lifetime of having little-to-no

control over one's work takes on a person. There is knowledge about

the workings of our economy, vital, relevant knowledge, that is

simply “invisible” to most economists because they've only seen

the view from the hilltop, not from the valley.

In order to overcome this blindness,

economists need to learn to listen to people who occupy other perches

in our economy, especially perches below their own. We would have

very different economic policy prescriptions if economists spent less

time in the tower and more time in the street, examining those things

which aren't visible from the faculty lounge.